In 1646, the Mohawk village of Ossernenon, near present-day Auriesville, New York, was scarcely welcoming territory for Christian missionaries. The Jesuit Fr. Isaac Jogues and the layman Jean de la Lande were killed there that year. Four years before, in the same village, Fr. Jogues had undergone such prolonged and brutal torture as to have been regarded as a “living martyr,” and his companion, René Goupil, had also been killed. Three of the eight North American martyrs watered the earth of this small Native American village with their blood, and one might have thought that the story ended there…But ten years later, in 1656, a girl was born in that same village to an Algonquin Christian mother, captured by the Mohawks and married to the chief of the Mohawk clan. The child’s parents and brother died in a smallpox epidemic that left her face scarred and her eyes damaged. “Tekakwitha,” she was called, “she who bumps into things” – a testimony to her impaired eyesight. The girl was adopted by her uncle, who became chief in turn.

Tekakwitha learned the traditional women’s arts of her tribe: making clothing, weaving baskets, preparing food, and helping with crops. She listened to the French priests who passed through her village, but she did not dare interact further with them. Not with her uncle and many of her clan so hostile to Christianity. At seventeen, Tekakwitha’s aunts pressured her to marry. She refused, suffering their taunts and punishments. At eighteen, she met a priest, Fr. Jacques de Lamberville, and at last felt free enough to say what was on her heart. She asked for baptism. The following year, Tekakwitha was baptized “Kateri,” the Mohawk form of the name “Catherine.” In this village that gave no welcome to Christians, she was a Christian. Kateri had known it would be hard. She prayed, eliciting contempt. She would not work on Sundays, and so received no food at all that day. She was treated little better than a slave. Soon, some of her fellow villagers accused her of sorcery. Kateri was in danger, and the priest advised her to set out on foot on a 200-mile journey to a Jesuit mission and Native Christian village south of Montreal.

Kateri arrived there in 1677. A Christian Iroquois woman, Anastasia, taught her to pray, to do penance, and to help those in need. Kateri embraced this new life with all her heart. She would pray alone in the woods, falling ever more in love with the Lord who had redeemed her, and did strenuous penance – of a style influenced by Mohawk traditions – asking the Lord to have mercy on her people who did not yet know him. The two priests and the inhabitants of the mission watched her with growing admiration. At 23, Kateri made a decision astonishing for a Mohawk maiden, whose well-being depended upon marriage. She told one of the priests, “I have deliberated enough. For a long time, my decision on what I will do has been made. I have consecrated myself to Jesus, Son of Mary. I have chosen Him for husband, and He alone will have me for wife.” She and two friends longed for some form of religious life, but the priest told them that they were still too young in the faith. So Kateri lived her ordinary life with a great love hidden in it. She belonged to her Lord, and in him, to all who were in need.

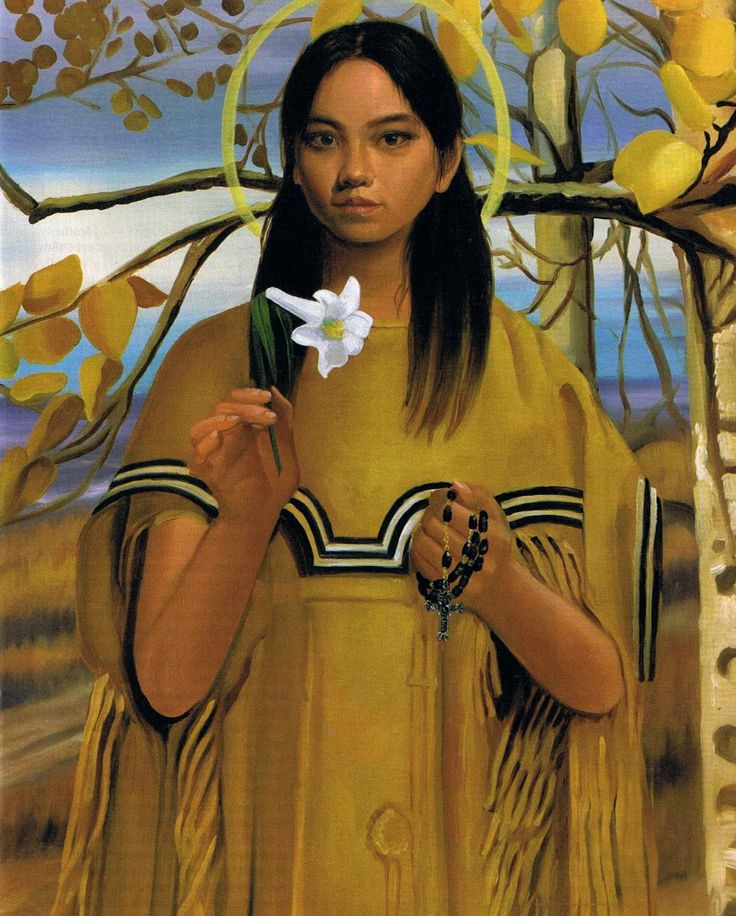

By Holy Week of 1680, Kateri’s health was failing. She died on Holy Wednesday. Those present said that her face became radiantly beautiful shortly after her death, and that her smallpox scars disappeared. Two Native women friends and a priest, Fr. Chauchetière, all said that she appeared to them within weeks of her death. On the gravestone of this spiritual daughter of the martyrs was written this epitaph: “Kateri Tekakwitha, Ownkeonweke Katsitsiio Teonsitsianekaron,” “The fairest flower that ever bloomed among red men.” In 2012, the “Lily of the Mohawks” became the first Native American to be declared a saint.

Source: https://www.vaticannews.va/en/saints/07/14/st--kateri-tekakwitha.html

"This blessed girl in saying to her companion, 'I will love thee in Heaven,' lost the power of speech. It had been a long time since she closed her eyes to created things. Her hearing, however, still remained, and was good to the last breath. It was noticed several times that when some acts were suggested to her she seemed to revive. When she was excited to the love of God, her whole face seemed to change. Every one wished to share in the devotion inspired by her dying countenance. It seemed more like the face of a person contemplating than like the face of one dying. In this state she remained until the last breath. Her breathing had been decreasing since nine or ten o'clock in the morning, and became gradually imperceptible. But her face did not change. One of the Fathers who was on his knees at her right side noticed a little trembling of the nerve on that side of her mouth, and she died as if she had gone to sleep. Those beside her were for a time in doubt of her death.

"When they felt certain that all was over, her eulogy was spoken in the cabin, to encourage others to imitate her. What her father confessor said, together with what they had seen, made them look upon her body as a precious relic. The simplicity of the Indians caused them to do more than there was need for on this occasion, as, for instance, to kiss her hands; to keep as a relic whatever had belonged to her; to pass the evening and the rest of the night near her; to watch her face, which changed little by little in less than a quarter of an hour. It inspired devotion, although her soul was separated from it. It appeared more beautiful than it had ever done when she was living. It gave joy, and fortified each one of them in the faith he had embraced. It was a new argument for belief with which God favored the Indians to give them a relish for the faith!" (Account of Kaveri's death by her friend)